Authoritarian personality (eros-thanatos)

The quintessential right-wing authoritarian is, unavoidably, Adolf Hitler.

Interestingly, the young Adolf Hitler was obsessed with art, not politics.

In some ways, Hitler seemed to have the classic artistic temperament (when first elected chancellor, he would stay up all night and sleep until the afternoon).

However, although Hitler might have had an artistic orientation, he did not fit the profile of the creative personality.

In fact, Hitler might have had a bold personal artistic agenda to purge creativity from art.

In this way, Hitler was a “White revolutionary” in the cultural realm when he was a young aspiring artist.

Later, Hitler transplant his agenda of cultural sterilization onto the political realm.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Architecture_of_Doom

.

This understanding might run against the modern equation of art with creativity.

For example, one classic interpretation of the true believer is that he feels that he is soiled, ruined, and worthless, and can only purify himself by dissolving his self in a mass movement.

In particular, the Third Reich was staffed with numerous failed artists who were (supposedly) creatively frustrated and who channeled their talents instead into mass spectacles.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_True_Believer

“The most incurably frustrated—and, therefore, the most vehement—among the permanent misfits are those with an unfulfilled craving for creative work. Both those who try to write, paint, compose, etcetera, and fail decisively, and those who after tasting the elation of creativeness feel a drying up of the creative flow within and know that never again will they produce aught worth-while, are alike in the grip of a desperate passion.”

Yet one hallmark of Nazi art (e.g., Leni Riefenstahl’s documentaries) is that while it can manifest the highest standards of aesthetic style and technique, it is unoriginal.

That might be the whole point of fascist art.

It’s not so much that fascists are creatively frustrated, it’s they have little creativity and are repelled by creativity.

The fascist desires to replace creative art with something more like industrial design.

Thus, Adolf Hitler’s watercolors are so conventional and devoid of life or innovation.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paintings_by_Adolf_Hitler

.

In a way, the fascist’s hatred of creativity is simply an extreme version of every society’s discomfort with, aversion to, and jealousy over innovation.

Creative art in particular is the biproduct of alienation, the artist’s gag reflex in response to society’s repulsiveness.

In return, society develops an allergic reaction to the creative artist.

The immune response in a modern society against the presence of creativity is to smother the creative artist with praise and money.

This is much like an oyster creating a pearl by encasing an irritant with layers of nacre.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/28/books/charles-webb-dead.html

“The public’s praise of creative people is a mask — a mask for jealousy or hatred.” By the couple’s various renunciations, he said, “We hope to make the point that the creative process is really a defense mechanism on the part of artists — that creativity is not a romantic notion.”

.

In the case of the fascist, behind this hostility to creativity there might be an exhaustion with life and its complexities, and an urge to return to a lower state of energy.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_drive

In classical Freudian psychoanalytic theory, the death drive (German: Todestrieb) is the drive toward death and destruction, often expressed through behaviors such as aggression, repetition compulsion, and self-destructiveness.

The death drive opposes Eros, the tendency toward survival, propagation, sex, and other creative, life-producing drives.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thanos

For example, Hitler’s favorite painting was Arnold Böcklin’s “Isle of the Dead”, which was mass produced for popular consumption.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isle_of_the_Dead_(painting)

Prints were very popular in central Europe in the early 20th century—Vladimir Nabokov observed in his 1936 novel Despair that they could be “found in every Berlin home”.

.

The greater point is that the right-wing authoritarian has certain personality traits that point toward authoritarianism (conventionality, stereotypical thinking, need for hierarchy).

These traits manifest themselves long before any trace of interest in politics.

That is not the case with the left-wing authoritarian.

.

The personality profile of left-wing authoritarian is quite different.

In fact, the tragic fall of the left-wing radical into authoritarianism is a classic theme in modern literature.

They start out as idealists and hippies, but circumstance compels them into the authoritarian mold.

However, there are hints early on that they are dogmatic, doctrinaire, and rigid, if not authoritarian.

For example, a classic literary figure would be the young idealistic Pavel Pavolovich “Pasha” Antipov in “Dr. Zhivago”.

His brutal experiences during the Russian Revolution transform him into the ruthless communist leader Strelnikov.

The big scar on his face is a symbol of his damaged soul.

How it started:

(“Dr. Zhivago”, 1957, peaceful protest)

Where it went:

(“Dr. Zhivago”, 1957, The personal life is dead in Russia.)

(“Eleni”, 1985, He was once an idealistic schoolteacher who believed in democracy…)

https://youtu.be/oYtl17EQYE8?t=945

(“Eleni”, 1985, … but eventually he became a hardened communist war criminal.)

https://youtu.be/oYtl17EQYE8?t=2094

The transformation of the revolutionary into an authoritarian might be found in mild form in the life of Steve Jobs.

Steve Jobs seemed to have the classic creative personality, although he may not have been artistically creative.

In his words, he was the maestro who “played the orchestra” — the orchestra being a major global corporation and its customers.

His oldest friends like Steve Wozniac said that Steve Jobs was originally a real hippie and a great guy and a fun person.

They said that over time, however, in order to realize his grand vision, Steve Jobs devolved into a typical ruthless, ambitious corporate-executive jerk.

.

Another dictator who might seem at first to fit the profile of the reluctant authoritarian might be Napoleon Bonaparte.

As a young man, Napoleon was a Corsican nationalist educated in France who eventually devoted himself to the French republican cause.

Superficially, at least, Napoleon fit the mold of a disappointed left-wing revolutionary who became a totalitarian ruler.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#Early_career

.

Actually, it’s more complicated than that.

According to Andrew Roberts, Napoleon was never a totalitarian ruler.

Napoleon represented the Enlightenment on horseback. His letters show a charm, humour and capacity for candid self-appraisal. He could lose his temper — volcanically so on occasion — but usually with some cause. Above all he was no totalitarian dictator, as many have been eager to suggest: he may have established an unprecedentedly efficient surveillance system, but he had no interest in controlling every aspect of his subjects’ lives. Nor did he want the lands he conquered to be ruled directly by Frenchmen. He believed that one can control foreign lands only by winning over the population and sought accordingly to present himself in terms that would make him sympathetic to the locals, feigning sympathy for their religion as a means to an end.

Napoleon was a military man who demanded order, and in his abhorrence of chaos, Napoleon was quick to crush rebellion before it spun out of control.

Napoleon perceived his own ruthlessness as humanitarian, both in intent and in outcome.

Politically, Napoleon believed in progress and desired change, and he saw chaos as an impediment to change.

For example, Napoleon lamented that every country in Europe would have otherwise had a democratic revolution were it not for the execution of the French monarch and his family.

So, Napoleon was a revolutionary who disapproved of violent revolution and chaos.

.

It gets even more complicated.

Napoleon’s commitment to social and political change was connected to his own powerful ambition.

Napoleon was a revolutionary in the American sense in that he sought to institutionalize equality of opportunity, not equality of condition.

That is, Napoleon wanted a new kind of social inequality — one based on merit.

For example, as a young man, Napoleon idolized the Corsican nationalist rebel leader Pasquale Paoli, who tore Corsica from its Genoan overlords and set about its modernization (e.g., writing a constitution).

In Napoleon’s mind, revolution at the service of renewal was justified.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pasquale_Paoli

In November 1755, the people of Corsica ratified a constitution that proclaimed Corsica a sovereign nation, independent from the Republic of Genoa. This was the first constitution written under Enlightenment principles. The new president and author of the constitution occupied himself with building a modern state; for example, he founded a university at Corte.

.

Corsican independence was brief.

Genoa secretly sold a Corsica that it no longer controlled to the French king.

Seeing that they had in effect lost control of Corsica, Genoa responded by selling Corsica to the French by secret treaty in 1764 and allowing Genovese troops to be replaced quietly by French ones. When all was ready in 1768 the French made a public announcement of the union of Corsica with France and proceeded to the reconquest.[6] Paoli fought a guerilla war from the mountains but in 1769 he was defeated in the Battle of Ponte Novu by vastly superior forces and took refuge in England. Corsica officially became a French province in 1770.

Napoleon’s father went over to the French side, and was recognized by the French as a minor aristocrat.

This was partly done out of personal ambition, but also because in contrast to the neglectful rule of Corsica by Genoa, French rule was an intrusive yet modernizing.

For the young Napoleon, modernization justified imperialism.

.

Again, Napoleon was a military man who believed in hierarchy, but a modern hierarchy open to talent.

Yet Napoleon did not conform to the profile of the authoritarian mentality, with its crudely stereotypical view of social reality and its lack of impulse control.

Martin van Creveld described him as “the most competent human being who ever lived”.

Napoleon directly overthrew remnants of feudalism in much of western Continental Europe. He liberalized property laws, ended seigneurial dues, abolished the guild of merchants and craftsmen to facilitate entrepreneurship, legalized divorce, closed the Jewish ghettos and made Jews equal to everyone else. The Inquisition ended as did the Holy Roman Empire. The power of church courts and religious authority was sharply reduced and equality under the law was proclaimed for all men.

[A]s summarized by British historian Andrew Roberts:

“The ideas that underpin our modern world—meritocracy, equality before the law, property rights, religious toleration, modern secular education, sound finances, and so on—were championed, consolidated, codified and geographically extended by Napoleon. To them he added a rational and efficient local administration, an end to rural banditry, the encouragement of science and the arts, the abolition of feudalism and the greatest codification of laws since the fall of the Roman Empire.”

.

It was argued above that the fascist is allergic to creativity, which reflects the fascists “death drive”, or exhaustion with life and desire for cessation of activity.

In contrast, Napoleon was a creative dynamo who concerned himself with transforming and micromanaging every detail of his empire.

One could argue that Napoleon was the creative version of a practical man of action (as opposed to the creative artist or the creative scholar or scientist).

.

The creative drive might be linked to Nietzsche’s concept of the “will to power” (der Wille zur Macht) — literally, the will to make or create.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Will_to_power

Some of the misconceptions of the will to power, including Nazi appropriation of Nietzsche’s philosophy, arise from overlooking Nietzsche’s distinction between Kraft (“force” or “strength”) and Macht (“power” or “might”).[2]Kraft is primordial strength that may be exercised by anything possessing it, while Macht is, within Nietzsche’s philosophy, closely tied to sublimation and “self-overcoming”, the conscious channeling of Kraft for creative purposes.

For Nietzsche, the will to power was an actual force at work in the physical universe.

Nietzsche’s theory is a brazen rejection of mainstream science, especially of mechanism.

Boscovich had rejected the idea of “materialistic atomism”, which Nietzsche calls “one of the best refuted theories there is”.[5] The idea of centers of force would become central to Nietzsche’s later theories of “will to power”.

.

The scientific version of the will to power sounds a lot like “vitalism“.

Vitalism is the belief that living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities.

This is because living entities contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things.

Where vitalism explicitly invokes a vital principle, that element is often referred to as the “vital spark,” “energy,” or “élan vital,” which some equate with the soul.

Today, vitalism is discredited.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitalism

In the 18th and 19th centuries vitalism was discussed among biologists, between those who felt that the known mechanics of physics would eventually explain the difference between life and non-life and vitalists who argued that the processes of life could not be reduced to a mechanistic process. Some vitalist biologists proposed testable hypotheses meant to show inadequacies with mechanistic explanations, but these experiments failed to provide support for vitalism. Biologists now consider vitalism in this sense to have been refuted by empirical evidence, and hence regard it either as a superseded scientific theory,[4] or, since the mid-20th century, as a pseudoscience.

.

For example, the French philosopher Henri Bergson developed the idea of the élan vital.

He was attempting to explain the question of self-organisation and spontaneous morphogenesis of things in an increasingly complex manner.

It is a hypothetical explanation for evolution and development of organisms, which Bergson linked closely with consciousness – the intuitive perception of experience and the flow of inner time.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89lan_vital

.

Nietzsche’s quasi-scientific version of the will to power differs from vitalism in that vitalism is explaining forms of life, whereas Nietzsche seems to attribute willpower to all things.

Insofar as Nietzsche is attributing the will to power to all phenomena, and not just to living organisms the way that vitalists do, Nietzsche might be engaged in a form of “panpsychism“.

In the philosophy of mind, panpsychism is the view that mind or a mindlike aspect is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality.

It is also described as a theory that “the mind is a fundamental feature of the world which exists throughout the universe.”

That is, all matter possesses some degree of consciousness.

Again, for Nietzsche, all things — including inanimate matter — possess will and creativity, and not merely mind or consciousness.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panpsychism

.

For Nietzsche, because entities in the natural world possess will, they might also have goals.

This might be a form of ” orthogenisis“.

Orthogenisis is the biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolve in a definite direction towards some goal (teleology) due to some internal mechanism or “driving force”.

Likewise, vitalism is related to orthogenisis insofar as it attempted to explain individual development and the evolution of species.

According to the theory, the largest-scale trends in evolution have an absolute goal such as increasing biological complexity.

Orthogenisis has been discredited scientifically, but in the popular mind, not only does it persist, it dominates.

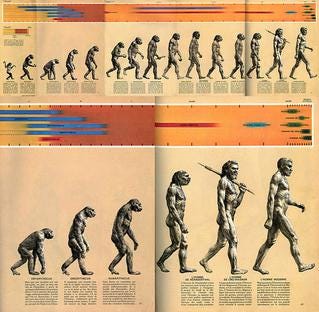

In fact, in popular culture, when people think of the theory of evolution, they imagine it in terms of “progress” toward a goal.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orthogenesis

The philosopher of biology Michael Ruse notes that in popular culture evolution and progress are synonyms, while the unintentionally misleading image of the March of Progress, from apes to modern humans, has been widely imitated.

Orthogenisis reflects a way of thinking about nature that can be traced back to the medieval Christian notion of a “great chain of being“.

The possibility of progress is embedded in the mediaeval great chain of being, with a linear sequence of forms from lowest to highest. The concept, indeed, had its roots in Aristotle’s biology, from insects that produced only a grub, to fish that laid eggs, and on up to animals with blood and live birth. The mediaeval chain, as in Ramon Lull‘s Ladder of Ascent and Descent of the Mind, 1305, added steps or levels above humans, with orders of angels reaching up to God at the top.

.

The Christian notion of the progress of the soul toward salvation therefore seems to find its echo in quite a few the ideas in question here:

the popular (and incorrect) notion of Darwinian evolution as progress toward a pre-established goal of increasing sophistication;

vitalist ideas that organisms possess a life force that drives them and their species toward levels of greater complexity.

Nietzsche’s belief that all things possess a creative will to power.

In fact, Nietzsche’s own emphasis on will seems to be of a Christian pedigree that Nietzsche himself does not seem to recognize.

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/N/bo3644846.html

But there is a flip side to Christianity’s idea of progress toward salvation, because the spirit of Christianity represents a retreat and withdrawal from … the world and life itself.

For Nietzsche, Christianity, as a religion of pity that disparages earthly life and preaches escape to a harmonious spiritual realm, manifested something like the drive to death.

In fact, even science, in postulating a theoretical realm of truth, resonates with the Christian yearning for a truer and more spiritual world beyond this one.

Nietzsche supposedly lost interest in his theory of the will to power because science is too reminiscent of a herd morality that resentfully invents and imposes universal laws.

That is, insofar as it attempts to be a scientific theory, Nietzsche’s own concept of the will to power is itself a symptom of degeneracy.

.

If the will to power as a scientific theory fizzled out even in Nietzsche’s mind, the psychological dimensions of the idea were explored and built upon by later psychologists.

Alfred Adler incorporated the will to power into his individual psychology. This can be contrasted to the other Viennese schools of psychotherapy: Sigmund Freud‘s pleasure principle (will to pleasure) and Viktor Frankl‘s logotherapy (will to meaning).

Notably, Freud connected the will to pleasure with the life instinct, in opposition to the death drive.

Freud ultimately developed his opposition between Libido, the life instinct, and the death drive.

Jungian psychology seems to align with Freud’s thinking on this issue.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Libido#Analytical_psychology

According to Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung, the libido is identified as the totality of psychic energy, not limited to sexual desire … and its antonym is the force of destruction termed mortido or destrudo.

In sum, Napoleon’s will to power was more of a practical expression of the creative life instinct — the inverse of Hitler’s death drive.