Amazon az "monopoly"

Amazon is an online department store that presents itself as an “open platform” that does not have to take responsibility for what it sells (pretending not to be the seller).

Therefore, Amazon is not too concerned about counterfeit or hazardous products because, presumably, it is up to the buyer to beware.

https://www.vox.com/recode/22810795/amazon-marketplace-prime-report

Amazon has always presented its Marketplace, where outside businesses sell products through Amazon’s platform, as one of its biggest success stories: mutually beneficial to Amazon, sellers, and customers alike. But a new report says those benefits are increasingly lopsided — in Amazon’s favor.

Amazon is milking its “sellers” — who are actually suppliers — for all they are worth.

The report, which comes from the nonprofit Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR), asserts that Amazon takes a larger and larger cut of sellers’ earnings through the various fees it levies on them. These fees have become so lucrative for Amazon that they now represent the company’s most profitable segment as well as its fastest-growing revenue stream, according to ILSR. And because sellers are paying Amazon high fees, customers may face inflated prices, even when they shop beyond Amazon’s borders.

Conceptually, one problem is the way that Amazon is perceived as a “monopoly” in the way that Amazon exploits its suppliers.

“Amazon is the only winner here,” Stacy Mitchell, ILSR co-director and author of the report, told Recode. “It’s exploiting its monopoly power over these small businesses to pocket a huge and growing cut of their revenue.”

Actually, dominating suppliers because they have no alternative is technically a “monopsony” and not a monopoly.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monopsony

In economics, a monopsony is a market structure in which a single buyer substantially controls the market as the major purchaser of goods and services offered by many would-be sellers.

The microeconomic theory of monopsony assumes a single entity to have market power over all sellers as the only purchaser of a good or service. This is a similar power to that of a monopolist, which can influence the price for its buyers in a monopoly, where multiple buyers have only one seller of a good or service available to purchase from.

.

We’ve been here before with Walmart.

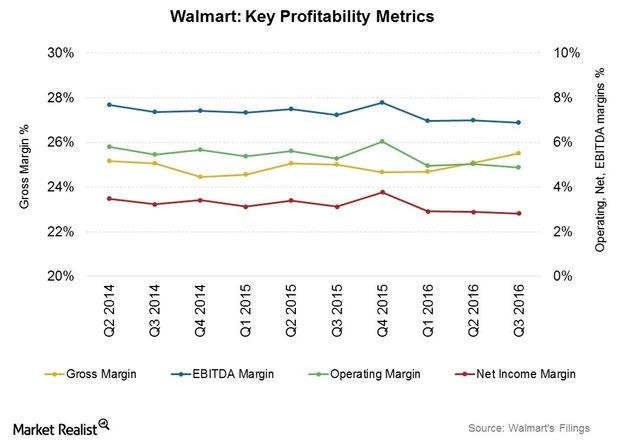

According to the internet, at first Walmart’s profit margins seem to be 25%, but on closer inspection that is the gross margin, and the net income margin is 3%.

Just as Walmart ruthlessly squeezes itself and its workers, it likewise forces its suppliers who don’t have much choice but to deal with Walmart to keep their prices down.

Thanks to its position as a tough monopsonist (as opposed to a monopolist), Walmart can provide the “everyday low prices” that it advertises.

.

Walmart has a cult-like commitment to being cheap.

When Henry Kissinger was given a tour of Walmart headquarters, for lunch he was taken into a back room and given a soda, a pre-made sandwich, and a bag of chips.

Kissinger looked up and said, “Now I understand Walmart.”

.

Back in the 1990s, Walmart and Microsoft were perceived as evil monopolies, but that fear and anger seems to have faded into memory.

There is reason to believe that eventually trepidation over and resentment toward Amazon will likewise dissipate.

This is because Amazon is both crucial to the American economy and because Amazon’s service is outrageously awesome, at least according to Farhad Manjoo.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/12/opinion/amazon-regulation.html

The Trouble With Breaking Up Amazon? Its Online Store Is So Good

Amazon created a retail paradise that protects itself from critics calling for stringent regulation.

Amazon is a genie of consumerist wishes, and it keeps growing more irresistible. The company’s online store has always been convenient and plentiful, but in the last year, Amazon significantly increased the speed at which it delivers products, with many items delivered overnight to its Prime members.

Amazon’s relentless high rate of innovation is evidence that it is in a competitive marketplace and is not a monopolist.

But in Amazon’s case, it might be growing increasingly difficult to persuade people that stringent regulation — and especially a breakup — will be a good thing. The trouble isn’t that it’s hard to make the case that Amazon is extremely big and powerful; the trouble is that even as Amazon gets bigger, it still faces relentless competition in the retail business, and is therefore not slowing in any obvious way to act like a lumbering monopoly of yore. The company keeps innovating — and as it does, the possible harms critics have long warned about may look increasingly distant to its customers.

What consumers may come to see in Amazon, instead, is what I’ve started to notice — it’s an inescapable, all-consuming retail paradise. Today, in the retail world Jeff Bezos built, it’s possible to get nearly anything you want, very quickly, for not much money, just about anywhere in the country, and probably to return it for free for just about any reason. And because Wal-Mart, Target, independent booksellers and others are all working furiously to match or exceed Amazon’s convenience, Amazon’s innovations are rippling across the retail industry.

Amazon’s excellence is what protects it from reform.

None of this is to suggest that Amazon’s growth is free of consequence. Last year The Wall Street Journal published a series of stories on the rising numbers of banned, unsafe, counterfeit or otherwise shady products flooding its store. A number of small companies have complained about Amazon’s efforts to copy their products or otherwise bully them into preferable terms. There are persistent reports about the dangers of Amazon’s delivery infrastructure — its contractors, racing to deliver packages as quickly as possible, have brought “chaos, exploitation, and danger to communities across America,” BuzzFeed reported last year.

Manjoo gives an example of how Amazon made it so easy to return one of his expensive purchases.

Only a mega-corporation in a highly competitive environment would be able and willing to do that.

Which brings me to the really amazing part: After using the lights for a couple of weeks, I packed them up and sent them back. Amazon is a trillion-dollar retailing phenomenon that has transformed almost everything about the way Americans shop, but sometimes it seems to operate as a charitable operation for well-off consumers who just want to try out this or that high-priced consumer fancy.

Consider all the resources Amazon put into my lighting purchase: The company had stocked its store with niche, highly-advanced electronics; it had spent billions on a shopping infrastructure capable of shipping those products to me overnight; and it had spent heavily on marketing, including doling out affiliate marketing fees to bloggers like Mr. Chapman, in order to bring customers like me to its store.

Yet, after all that, I’d decided to use the company essentially as a kind of product lending library. I purchased a variety of expensive items I had only marginal interest in keeping for the long-term, I’d opened the boxes and got my sticky hands all over them, and when I grew tired of them, I sent them back like so much used laundry.

How much had the company made on me? Not a penny — at least, not that time. Which, of course, is the bet: The more absurdly convenient Amazon is to me, the more likely I will be to spend more of my money there next time. And to balk, it hopes, when the next president floats a plan to break apart the everything store.

.

There might be a contradiction of sorts between Amazon’s generous return policy and its pretense to be an “open platform”.

A true open platform would presumably assist in connecting a dissatisfied customer with the seller.

But the elaborateness and efficiency of Amazon’s return policy suggests that Amazon is really the true seller and the other parties are pretty much suppliers.

Again, Amazon is a department store pretending to be an open platform, and this suggests one path of regulating Amazon distinct from treating it like a monopoly.